When it comes to strength training and conditioning I have very strong opinions on the subject. Friends of mine in the industry often joke with me “Careful Don't Get Him Started”.

Well hang on cuz it's Too Late And You Got Me Started...Here are just some of my thoughts on important points for strength coaches and athletes to ponder.

Straight-ahead sprinting and change-of-direction agility drills elicit a

(stretch-shortening) effect. Therefore, whenever you're sprinting and doing agility drills, your doing plyometrics. No need to spend an inordinate amount of time jumping on and off boxes.

If you're doing squats without a weight belt, lunges, dead lifts, RDLs / stiff-leg dead lifts, overhead presses, bent-over rows, conventional trunk flexion and rotation abdominal exercises or any on-your-feet exercise, your engaging your Mid-Section

You don't need a 20 minute Swiss ball or medicine ball-on-a-rope routine or a series of funky Pilate's moves. Work your entire body -- including basic Mid-Section exercises -- and move on.

exercise is any exercise you do that makes you stronger. Read: any exercise that creates overload on a muscle and is done progressively is

Last time I checked, ALL muscle groups were important at some point for proper athletic skill execution and injury prevention.

Speed gadgets and gimmicks such as parachutes, rubber tubing, sleds, weighted vests, and the like are nothing exceptional. They by themselves will not make you

after their use. They can be used for variety in a conditioning program (repeated use can create fatigue), but that's about it. It is a fact that running with weight or against resistance alters running mechanics from those used in unweighted sprinting you'll experience during a game (sport-specific). Therefore, keep your running both sport and energy system-specific by replicating the situations / runs you'll face in competition.

Increasing strength = increasing power. It's still ridiculous that we have to address this issue with all that we know today. It's simple physics: power = work (force x distance) / time. It's the rate of work done relative to time. The work component is effected by force output. Stronger muscles = greater force production. Thus strength training (heavy, slower moving by nature resistances) is vital for increasing power output. The time component is simply a consciously-controlled, nerve impulse issue: if I want to explode or react quickly, I consciously do it. It's a timing issue that is improved through the practice of exploding or reacting quickly via inter- and intra-muscular synchronization and coordination,

UNABATED BY RESISTANCE TO ASSURE THE QUICKEST/FASTEST SPEED OF MOVEMENT.

If one attempts to improve the speed of movement (the time factor of the power equation) in the weight room, they face a huge dilemma: if they want a fast (relative) movement speed, the resistance used will have to be light in order for it to move

However, the lighter the resistance (i.e., a 45 lb. bar), the faster it can move but the fewer muscle fibers recruited and overloaded (a low demand). If more resistance is added to the bar, the slower the movement speed, but with a greater number of muscle fibers recruited. More resistance added means a further slowing of movement speed, but with greater fiber involvement (read: more fast/type 2, greater force generating fibers activated due to a greater demand). So, where do you draw the line on the optimal resistance needed for enhancing the time factor of the power equation? The answer: heavier rather than lighter. Remember, the speed of movement that one uses to build power is independent of the speed of movement one uses to demonstrate power! Build force production (strength) in the weight room with naturally heavy, slower moving, greater muscle fiber recruiting resistances. Work on the time aspect outside the weight room using sport-specific, exact speed, consciously explosive/quicker drills.

"FAST TWITCH / SLOW TWITCH"

Slow twitch / type 1 muscle fibers are only

relative to fast twitch / type 2 muscle fibers. That is, fast twitch / type 2 fibers are larger, stronger and faster to contract as compared to type 1 / slow fibers, but if the demand is low (i.e., a vertical jump...body weight-only), the slow twitch / type 1 fibers can move the body

for this task. This explains why one can do body weight explosive efforts for a number of repetitions. Fast twitch/type 2 fibers dominate only when muscle tension and demand are high (i.e., a heavy squat), but slow/type 1 fibers are still involved.

"OLYMPIC LIFTING FOR OTHER SPORTS"

Olympic lifting is a great sport. However, when it comes to training for other sports, these lifts

do not transfer to improve other sport skills,

are not necessary for maximal power development,

limit the magnitude of overload on the larger muscles involved (lower body) due to weak link muscles (upper body),

violate safe and proper lifting techniques due to the nature of the lifts and

can be time-consuming regarding teaching and learning. If you do them, be careful, but remember the other exercises you perform (to address over-all body strength) will improve power potential, safely.

"OPTIMAL NUMBER OF SETS PER EXERCISE"

One does not have to perform mega-multiple sets (5+) for each muscle group to increase strength. If working hard – very hard – minimal sets will work, and up to three can be more than enough for some. Most people who disagree with the minimal set approach have never experienced it. If they did, they obviously didn't work as hard as they could have.

I have read all the one-set vs. more-than-one-set approach to optimal strength training research and I have concluded this:

For the average trainee out there in 2022, doing SOMETHING (one set, all-out) is 100% better than doing nothing. Think about that.

Performing one set, all-out, followed by an additional set or another set (3 total) again going all out, will result in diminishing returns. That is, for each set performed to volitional muscular fatigue, it will be impossible to recruit the higher threshold type two fibers in forthcoming sets due to progressive fatigue. Any recruited and overloaded muscle fiber have then been "spent" thus the more-enduring intermediate and lower threshold fibers are still available, but with the inability to sustain the movement of a relatively heavy resistance for continued repetitions.

1)

It's not about the number of sets performed. It's the quality / effort*

exuded. Go all-out (voluntary fiber fatigue) and the job is done.

*Creating high tension in the muscle fibers and working to momentary muscular failure involves the greatest amount of relative muscle tissue. Effort (working to fatigue) and using good form (controlled movement with no bouncing or jerking) are important here. If in doubt, slow it down and aim for maximum repetitions (safely).

2)

Recovery. If the above occurs, allow time for adaptation, both clock time and nutritional time (adequate protein and other micro-nutrients).

The question of what is the optimal number sets will always be a topic of perpetual discussion. If you are truly willing to explore, than beginning with only one working set is the logical place to start.

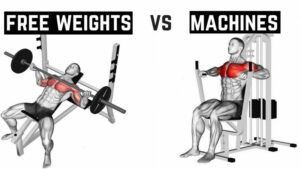

Machines Vs Free Weights:

The majority of weight rooms today consist of mostly power racks and benches, with machines being considered inferior or less “FUNCTIONAL”.

The scientific literature says your muscles can’t distinguish what’s providing the resistance—whether you stimulate them with a barbell or a machine*, you’ll get roughly the same result. When conducting training for regular folks, seniors, younger athletes, people who don’t need, want or require the specific skills of barbell training, machines are often a safer, better option.

*Muscle overload can be applied with a variety of tools: barbells, dumbbells, machines, manually applied resistance, body weight, sand bags, etc. Anything that can create high tension in the muscles can be used.

“ What’s your training philosophy?”

It may sound a little silly, but I don’t have one. A philosophy is a system of beliefs, and I choose, instead, to take a science-based approach to resistance training using nothing but the most recent valid, reliable, research.

Frequency recommendations:

Generally, when working with young, fit, motivated athletes, we train the entire body twice a week, and our athletes can come in a third time if they choose. But if they’re busting it out twice a week, that’s usually all they need. In-season, we’ll cut that back to one total-body workout and maybe one upper-body workout each week.

What is the most catastrophic injury an athlete can suffer in any sport? A cervical spine injury. Since we strength train mainly to help athletes avoid injury, my go-to exercises in the weight room are neck flexion and neck extension and shrugging movements. In addition to building muscle with these movements, athletes are strengthening their connective tissue and increasing bone mineral density in the cassettes of their cervical spine, which leads to a more structurally sound neck. I see building a stronger neck as a critical concussion prevention tool.

Nowadays, the stereotypical strength coach is someone who yells and screams all the time. It’s really sad, because when the rubber hits the road, you motivate people by forming sincere, unique relationships. You have to make a human connection and gain an athlete’s trust. Once you do that, they’ll do anything you ask.

High Tension Strength Training

No matter what your base approach to strength training involves, an indisputable tenet of hypertrophy (size increases) in muscle tissue indicates that tension must be created and maintained in the targeted area for the duration of the set. In other words, there comes a time when your athletes must engage in strength training techniques that require all out, or near all out efforts to complete the assigned rep range (e.g., 6-8 reps) or target number (e.g., 8 reps). This is a very metabolically demanding method of strength training that provides a high level of stimulation to muscle tissue.

When is an athlete ready for this type of training? From an age standpoint, an athlete in his freshmen year of high school should be physically ready to partake in this type of training, provided he / she has an adequate training background. We would wait until the athlete has been oriented in your current program and has been training with some degree of consistency and proficiency for several months.

Obviously, on certain movements, such as barbell squats, barbell / dumbbell bench press and incline press, and a short list of others, caution is the operative word when attempting those last few, most intense reps. Taking these particular exercises to the point of complete muscular fatigue is neither recommended or sensible. With practice, excellent coaching, precise documentation, and a generous allotment of common sense, a workable weight can be married to a rep assignment that elicits a great muscular effort within safe boundaries. Some free weight movements and most machine exercises can be performed in this manner. The beauty of the high tension approach is that it doesn’t need to be performed on every training day. Once a week, or even bi-weekly bouts will extract noticeable gains.

The coach’s base methods can be executed on the other weekly training days.

Here are some bullet points on implementing a high tension workout:

- Choose primarily multi-joint exercises – those that enable more than one joint and recruit the larger, more size receptive musculature (e.g., deadlift, leg press, Lat pulldown, DB rows, chin-ups, dips, various machine pressing and pulling movements, etc.).

- Through trial and error or a percentage of an estimated maximum (approximately 75-85%) choose a weight that allows for 6-10 reps.

- Perform the reps in a fashion where the positive (raising) phase is executed with enough force to generate steady movement, but not so rapidly as to lose control. Execute a more controlled negative (lowering) phase to heighten the intensity and prolong the tension within the targeted musculature.

- If the weight selection is correct, the last few reps should be very difficult to perform without deterioration in technique. Excellent exercise techniques are crucial, regardless of the movement being performed.

- Eight to twelve and up to fifteen to twenty total sets can be performed, in any arrangement you prefer. Multiple sets of the chosen movements can be executed, or more exercises with reduced set schemes can be incorporated. Over time, a mixture of multiple set and limited set routines can be rotated for variety.

- Recovery periods between sets can range from 2-3 minutes in the initial stages, and be gradually reduced to 1 minute as the athletes adjust and adapt to the metabolic intensity of the workouts.

For more ideas about creating simple effective strength training and conditioning programs check back here frequently or visit us at:

www.tntstrength.com

Register

your name and email address on the site so you can be kept up-to-date on the latest news from TNT Strength.

TNT has over 40 years of combined fitness experience, so if you’re looking for a coach who can train you in person in our Oakland California Studio or online from anywhere in the world, visit our online training page

to book a consultation.